Debugging

Debugging is the process of locating and fixing bugs in programs. This is one of the programmer's least liked activities. It can be frustrating, labor intensive, and sometimes downright painful. As programmers mature, they realized that it is often better to write the code carefully and avoid bugs that it is to go through the pain of finding and fixing the bugs.

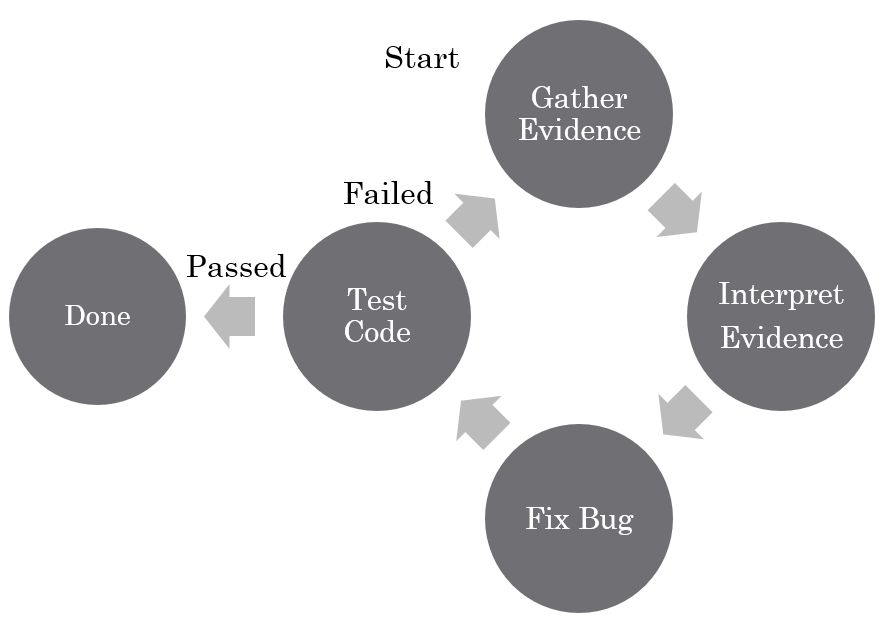

The debugging process is similar to being a detective. You take a look at your program and you see that it is not performing as it should. The fact that it's not performing correctly is evidence which you can then use to try and determine the location of the bug. In many cases the evidence that is immediately available is not sufficient to locate the bug and you have to gain more evidence. The techniques to gain more evidence include:

inserting print statements to determine where the code is executing and what the values of variables are.

Creating a log file which will capture the output of numerous print statements to give you an up to date picture of what the software has been doing.

Using an interactive debugger to stop the program in mid execution and examine the state of the variables. Debuggers also allow you to resume execution, step-by-step, and watch the program as it executes to examine the values of the variables as they change during execution.

Which of these debugging techniques you use depends greatly on the tools you have available to you as well as the type of program you are trying to debug. For a simple program that is relatively short, inserting some print statements might be the simplest way to gather the evidence. In other cases, you might have a distributed program which is running on multiple computers over a network. In this situation, it is difficult to gather all the data from the different machines and log files are the best solution. For programs running on a single machine that are more complicated, interactive debuggers are usually the best choice. Nothing says you have to use just one technique since you can combine different techniques depending on the type of problem you're dealing with.

One of the difficulties of a print statement is that output is usually buffered. This means that when a program terminates suddenly output can be left in a buffer and never actually print on the screen or other output device. This can cause the programmer to believe that the code was in a different position than it really was when it terminated. To get around this problem, you should flush the output streams regularly to make sure that no output is left in the buffers when the program terminates abnormally.

Types of Errors

Computers have two very different types of errors. One is the syntactic error which happens when your program does not follow the rules of the programming language. Syntactic errors are detected by the compiler at compile time and generate either a warning or an error. Warnings do not stop the execution of your program but they do indicate that the compiler has detected that you are doing something very unusual. Many students ignore warnings because they do not stop the program from executing. However, warnings should not be ignored as they often give a clue as to a problem which has yet to manifest itself. Errors actually stop the compiler from generating the code and they are far more serious violations of the programming language syntax. Errors must be corrected before you can generate working code.

Fortunately, the compiler produces good error messages which usually tell you the exact line that has the problem and give an indication of what the problem is. While these messages might appear cryptic when you first see them, as you get more experienced, you will find that they are actually quite easy to decipher.

C compilers are very good at generating a large number of compile time error messages. These messages are often much larger than the actual cause of the messages. Often, many messages can be generated from something as simple as forgetting to include a header file. Just because the compiler says your program has 200 error messages doesn't mean that there are 200 separate errors you need to fix. It could be that there are only about a dozen. It is common for an error in a header file to be included into multiple implementation files resulting in the replication of error messages.

The other type of error is a runtime error or what we call a semantic error. These occur because your program doesn't do the right thing. You detect them when you run the program by observing that the program fails or by observing that it produces incorrect output. These semantic errors are often far more difficult to find than the syntactic errors. We will not spend a lot of time on syntactic errors in this course and will concentrate primarily on semantic errors.

Warnings

In addition to compilation errors, compilers produce warnings. These are not severe enough to stop comiplation but serve to tell the programmer that something unusual is being done by the programmer or that the compiler is making an automatic conversion or has made an assumption. Many beginning programmers ignore these messages since they do not stop comiplation. This is a mistake since they often contain important information that points to what will become a sematic error in the running program. Programmers ignore wanrings at their peril! Each warning should be examined, understood and corrected, if possible. Programmers should strive for programs that produce no warnings.

Link Errors

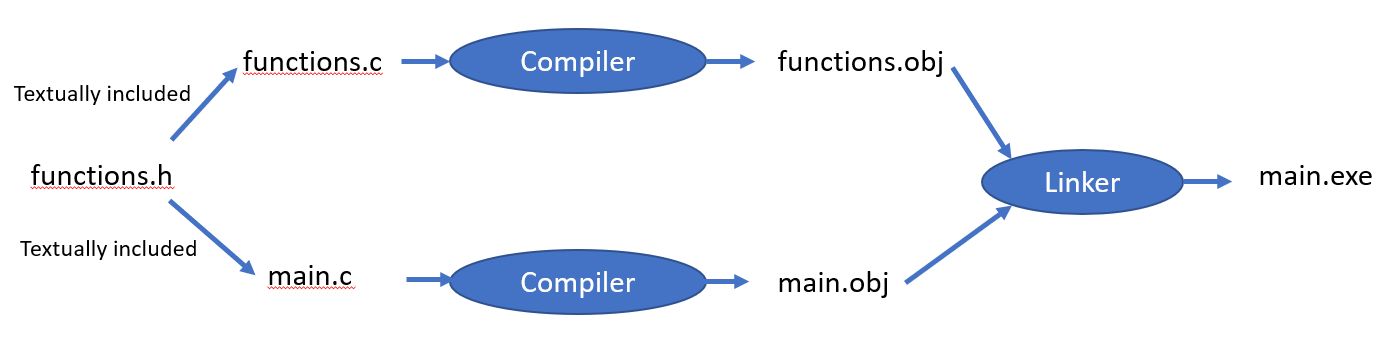

Another source of errors are from the linker. To understand what these messages mean, we need to review the process of separate compilation, depicted below.

Once you break your program into separate .c source code files, you will be using separate compilation. This means that each source file is compiled separately to produce an object file. The object file is the compiled version of the code, represented as native instructions for your particular CPU. Since your main.c references functions in functions.c, these references need to be fixed so that main knows where to find the functions it calls. Putting the object files together and fixing the reference to functions in other object files is the job of a program called the linker.

The linker produces its own error messages which say one of two things:

- It was looking for something and could not find it,

- It was looking for something and found two or more of it.

When the linker goes looking for a variable or function, it expects to find one of what it is looking for. If it finds zero, it cannot complete the link process as part of the code is missing. If it finds two definitions of the same thing, then it is left not knowing which it should use so it abandons the linking process.

All linker errors come down to one of these two errors. The trouble is that the messages from the linker are often not clear. This is particularly a problem when working with template-based C++ code where the messages can span multiple lines. What you need to remember is that it is saying that it either did not find something or found two of something. Then, read the message carefully looking for names that you recognize that indicate what is missing or duplicated.

Many people wonder why the header files are not compiled. Header files are textually included in the C implementation files, which are then compiled. This means that your header functions are compiled, but only by being included in the implementation files.

The common reasons for getting a message from the linker are:

- you wrote the declaration for a function or variable and forgot to write the definition,

- you forgot you already defined a function or variable and defined it twice,

- you accidentally used the same name in different parts of the program,

- you omitted one of the object files that should have been sent to the linker.

It is important that you understand the difference between declaration and definition. When you write the function prototype in a header file or an implementation file, it looks like this:

int square(const int n);

The declaration tells the compiler:

- the name of the function,

- the number and type of the parameters,

- the type returned by the function.

This information allows the compiler to check the types when the function is called. This is why you include header files in implementation files that will be calling the functions declared in the header files -- so the types of the parameters and return type can be checked. What we have not seen so far is the definition of the function, where we actually provide the code for the function. This is placed in an implementation file, as shown below.

int square(const int n)

{

return n * n;

}

This defines what the function does and this definition is what the linker is looking for. You get an error if the linker finds zero definitions of a function or if it finds two or more definitions.

Something similar can happen with variables. Let's say you have a header file in which you define a variable.

#ifndef HEADER_H

#define HEADER_H

int n;

#endif

This does not declare the variable n, but defines it. This means that it allocates memory for it and associates the memory address with the name n. If you include this into two implementation files, it will allocate memory for the same variable twice. When the object files are sent to the linker, it will find two areas of memory associated with the same variable and not know which one to use, resulting in a linker error. The way to overcome this problem is to replace the definition of the variable in the header file with a declaration.

#ifndef HEADER_H

#define HEADER_H

extern int n;

#endif

The keyword extern indicates that this is just type information for the variable and that it will be defined elsewhere. This transforms a defintion into a declaration. While you can delcare the same function or variable multiple times, you can only define them once. Therefore, the variable n must be declared in exactly one of the implementation files. While you might think, "But I use it in two implementation files...", the linker will fix it up so that all implementation code points to the single defined memory location for the variable.

Debugging Techniques

There are numerous techniques you can use to try and track down the bugs in a program. When you are tracking down bugs, you need to know several pieces of information:

Where the program was executing when the bug occurred,

Whether the point of termination was where the bug occurred or whether the bug occurred long before the program terminated,

In many cases the program will not terminate but rather simply produce incorrect results. In situations like this you have to start looking at the code that calculated those results and try and figure out what went wrong with the calculations.

Often, when you see a program executing a certain piece of code, you are mystified as how it got to execute that piece of code. In situations like this you try and answer the question "how did I end up executing this piece of code?".

Often you need to see the values of individual variables and watch them change to figure out exactly what is going wrong.

Debugging can be very complicated and many bugs are elusive and very difficult to track down. Finding these bugs can be both frustrating and very time consuming. The key to finding them is cleverness and persistence. Sometimes a bug can take weeks to find. Fortunately, as you become more experienced, you get better at finding bugs and getting an intuition as to what causes a particular type of problem.

Debugging Clues

As you gain experience, you will find that there are certain giveaways as to what might be the source of the bug. Bugs which totally stump novice programmers are often solved in a couple of minutes by experienced programmers. Below I will go through some of the most common reasons for bugs and how to identify them.

Segmentation Faults

Modern computers and operating systems have the concept of protected memory. This means that they are easily able to recognize memory which is allocated for use by your program versus memory which has been allocated for use by another program. If your program attempts to access memory that has been not allocated to it, a segmentation fault is generated. The segmentation fault normally results in the termination of the program. The most common reasons for a segmentation fault are:

Having subscripts which run off the end of an array. If the array is stored near the boundary of your program and another program then incorrect subscripts can cause you to access the memory outside your own program resulting in a segmentation fault. Looking for bad subscripts on arrays is one of the first things you should do.

Another common reason for segmentation faults is a bad address. When using pointers, you can generate a pointer which points to memory outside the memory allocated to your program. This results from some an error in calculating the pointer. Since the pointer accesses memory outside of your program's memory, it generates a segmentation fault.

The third, and less common reason for a segmentation fault, would be an uninitialised variable. Some compilers make it difficult to have uninitialized variables while other compilers allow the use of uninitialized variables. Uninitialized variables can have random values depending on where they occur. In general, we treat an initialized variable as having a random value and, if this variable is used as a pointer, it can often address memory outside of your program.

one of the most common values to cause a segmentation fault is a NULL pointer. NULL has the value zero and this references part of the operating system. If you find that the pointer that caused the segmentation fault has the value of NULL or zero then you should figure out why it was not calculated to have the correct value.

Bus Error

The bus error is similar to the segmentation fault in that it is in illegal memory access. The difference between the two is that segmentation fault address is valid memory that is not allocated to your program whereas a bus error access is memory which does not exist. The reasons for the bus error are similar to that of a segmentation fault and you should follow them down using the same debugging techniques.

Another problem which can cause a bus error is attempting to access memory which has been deallocated. Once you start doing dynamic memory allocation, it is possible for you to keep pointers to memory that you've already deallocated. Attempting to use these pointers to access the memory which has been deallocated can result in a segmentation fault.

Random Behaviour

Random behavior where your program behaves differently every time it is run is almost always a result of uninitialized variables. The reason the program is behaving randomly is because every time it accesses a variable it gets the value that was in that location previously. Since that value is probably close to random, it causes your program to behave in a different way every time it is run. Whenever you see random behavior, the first thing to look for is uninitialized variables.

Program Executes The Wrong Code

Occasionally, you will find that your program is executing code that it should have been executing. When you look at a stack trace, you might find part of a stack trace missing. These are symptoms that there is a much larger problem in your program. It means that your program took a random jump and ended up in some code that it shouldn't have. This could be a bad pointer or it could be some strange problem with the program. This is one of the most difficult and challenging bugs to identify.

My Variable Just Changed it’s Value

if you ever find that a variable seems to have changed its value on its own, then some other piece of code must have changed the value. Tracking down this other piece of code can be particularly difficult. Often it is the result of running off the end of an array or using a bad pointer which does not reach outside your memory space for your program but just accesses valid memory within your program.

Compilers generally layout memory linearly as the variables are declared. Take a look at where you declared the variable whose value is being changed. If you find it is declared right before or after an array then check to make sure that the bounds of those arrays are not being exceeded. On the other hand, if it is caused by a bad pointer, it can be very difficult to locate where the bad pointer was generated. Some debuggers have a watch feature where you can watch a particular memory location and have the debugger notify you whenever that location is changed. This is one of the few techniques that will help you debug this type of problem.

My Program Works on One Compiler and Fails on Another

Most students think that this is a fault of the computer or the compiler. While it is possible that the computer or the compiler can make mistakes this is extremely rare. These compilers are used by thousands and thousands of people every day and if there is a bug in them it is found and corrected quickly. It is far more likely that the problem is in your program.

The reasons why programs behave differently on different compilers and operating systems is because different compilers on different operating systems do different things. For example, on Unix operating systems, memory is usually not zeroed out before being given to a new program. On Windows you could always depend on your memory to have been zeroed out before being handed to your program. The other big difference is in how compilers layout and allocate memory. Some compilers will do byte alignment where they extend variables to give them a little extra space for the word size of a particular computer. If you switch to a computer with a different word size then it will have different padding between variables to make sure that the variables start on a word boundary. This small difference in spacing can result in a program working on one compiler but failing on another compiler. The real reason for this is most likely you've either got in index exceeding the bounds of an array or an invalid pointer. On one of the compilers this bad memory address simply accesses some of the empty space between the variables used for padding whereas in the other compiler it accesses a real variable and corrupts its value. The fault for this lies not with the compilers but rather with your program. If your program was working perfectly it would work perfectly on both compilers.

My Program Just Stopped!

If you find that your program stops in the middle of execution for no reason, you should consider the possibility that you might have handled an exception or a signal. C programs allow you to install signal handlers that will intercept signals sent to your program and do something with them. These signal handlers can catch segmentation faults and bus errors and allow the program to continue to execute. The reason the signal handlers are available is to allow the programmer to catch erroneous conditions and to try and do something intelligent to recover from them. Many students find the signals that are causing the program to stop execution to be very annoying and they install a signal handler which does nothing. This can have very strange effects. It creates a program which should have stopped yet is continuing to blunder along. What exactly will happen with this program is almost impossible to predict.

Most languages have an exception facility where code which has a problem will throw an exception. Exceptions can be caught in a try-catch statement and then handled in an effort to recover from the error. Once again, many programmers find these errors inconvenient so they install a try catch which catches the exceptions and does nothing. If your program just stops without any error messages, then you should consider the possibility that you have put some erroneous code inside a try-catch, it throws an exception, you catch the exception, and do nothing. The operating system then terminates your program and it has the appearance that it just stopped. Catching an exception and doing nothing is usually a bad idea.

Memory Errors

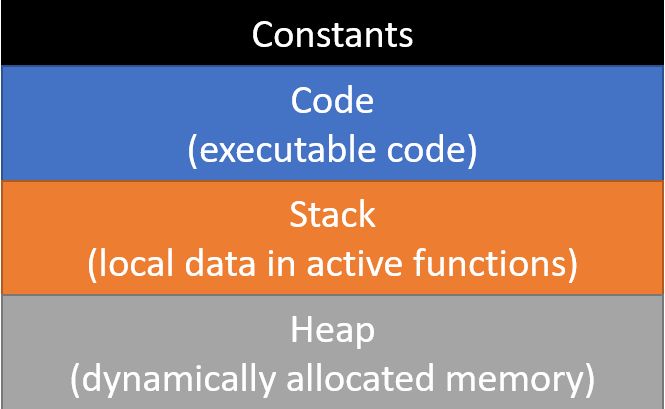

Computer memory for an application is divided into four main parts:

- an area for constants. When you create a constant in a program, it is stored directly in the image on disk. This means that the constants are loaded into memory along with the executable code. This saves having to assign values to them at run-time since their values are assigned as part of the loading of the program.

- An area holding the executable code. This is the binary representation of the code you wrote that is ready to run.

- A stack onto which stack frames are placed every time a function is called. The stack frames contain the memory for all the local variables inside the function. Each time a function is called, a new stack frame is created for it and, when the function returns, the stack frame is removed from the run-time stack. The next function call will place a new frame on the stack which will overwrite a previous stack frame, destroying any values stored there. When you inherit space on the stack which was used previously, it will have the values from the previous function in it and you need to initialize all your variables to avoid getting random values in them.

- A heap from which memory can be dynamically allocated. This is what is used when you use the new and delete operators in C++ or the allocate and free functions in C. The heap is automatically managed to find memory of the size you need and to make memory that was freed available for reuse. These algorithms get very confused if you delete the same memory twice, leading to unpredictable errors.

Some languages, like Java and C#, offer managed memory. This means that there is a new operator to allocate an object but no delete operator to make the memory available again. These languages keep a count of the number of references to each dynamically allocated variable. When that count drops to zero, no one is using the variable anymore and it is marked available for reuse. A separate thread runs a garbage collector which is responsible for gathering up these variables and making them available to be used again. Some of these languages allow you to give hints to the garbage collector to run and reclaim memory. This can give your program more heap memory when it starts to run out.

One thing that can go wrong with memory is to exhaust the stack space. This happens because you've called so many functions that you have literally used up all the memory allocated for the runtime stack. The possible reasons for this include:

- You're storing a very large number of local variables or large arrays as local variables inside the functions. If this is the case, you should consider reducing the number of variables or using dynamic allocation to allocate the space from the heap rather than from the stack.

- You have a case of infinite recursion. Recursion is defined as when a function calls itself. This might be either directly where the function calls itself or indirectly where a function calls another function which then calls the original function. Regardless of how it happens, if you are in a situation where you call a function recursively forever, you eventually exhaust the stack space. Finding infinite recursion is relatively easy because if you put a few print statements in the functions you will find that you print out large numbers of them. Once you find the location of recursion, find a way to break it and your problem will be solved.

You could also exhaust the heap memory. Exhausting heap memory occurs because you allocated too much memory, which is actually fairly rare, or you have a memory leak. A memory leak is when you allocate memory but you never free it. This is actually very simple to do in the C language and it's hard to find out where it's occurring and to avoid it. Getting large C and C++ applications so that they do not have memory leaks is actually a difficult task. There are automated tools that can try and detect where this might be occurring but the best thing to do is to use smart pointers that automatically deallocate heap memory when it goes out of scope. While this solves the problem of heap memory which is only needed for the lifetime of a function, it doesn't do much to solve problems of heap memory which is needed for a longer duration.

The other problem that can occur with the heap is that if you delete the same memory twice or you try and use a pointer to memory which has already been deleted, you can end up with some very strange errors. These errors can be very difficult to locate and fix.

Numeric Problems

Several problems can occur when doing arithmetic calculations. These include:

- Incorrect Results - You might have performed a calculation in integer arithmetic and lost the fractional part of a number.

- Results start OK but then change sign - Numbers are stored in a format where if a number gets too big, it wraps around and becomes negative. The problem is that you are using too small a type to store the number.

- Inf - this means that the result of the calculation is infinity. Look for division by zero or other arithmetic problem.

- NaN - Not a Number. Often due to divide by zero but might be for another reason. Regardless, the value is not a valid number.

- Prints a strange value - Check your format codes to make sure you are not printing an int as a float or similar type problem in a printf.

Non-Zero Return Code

This is difficult to debug since it could be caused by many things. Consider:

- divide by zero

- out of memory

You really need to narrow down the cause of the bug. Try running the code and stopping at various points until you hit the bug. This might give a clue as to where it is occurring. Repeatedly narrow it down until you find the line on which it occurs.