Other Debugging Tools

There are other debugging tools, most of which are less frequently used than print statements and interactive debuggers. in the sections below we will examine some of these tools and when it might be appropriate to use them.

Log Files

Log files are simply files containing text and values written out by programs as they execute. Log files have the advantage that the information can be gathered whether the programmer is actually sitting there watching the program execute or not. Log files can be gathered over a long period of time and can be triggered to gather output only when specific erroneous conditions arise. Log files can gather valuable information to aid in the debugging of a problem which happens in a production system. Trying to debug a problem that happens in a production system, long after the problem has happened, is very difficult without log output to help you.

Another situation where log output is very useful is when you are working on distributed programs. These are programs which work on many computers and make remote function calls from one computer to another. Tracking this sort of program is very difficult simply because different parts of the program are actually executing on different computers. One of the ways to deal with this situation is too have every computer write to a central log file located on the Internet. You could have a server setup to gather these inputs and write them to a file. The other way to do this would be to have each computer write its own log file to its own file system and then to examine these later.

Log files typically contain the information that identifies each line written to the log file. Although the information included at the start of any line may very, you might want to include the following information.

- The name of the computer producing the output,

- The name of the program producing the output,

- The ID of the thread producing the output,

- The timestamp of the output to the millisecond,

- The name of the function producing the output,

- Including the name of the file producing the output and the line number producing the output. Note that this information can be obtained from the preprocessor macros __FILE__ and __LINE__ which will be replaced by the file name as a string in double quotes and the line number as an integer. These reflect the line in the file and can be easily added to a print statement.

- An informational message that might show the values of variables, describe an exception caught or an unusual situation which has occurred. If the log file is being used on a program which is known to have bugs in it and is not in production, then you might want to flush the output stream after every line is written to the log file to make sure that all of the output reaches the file. While this will guarantee that all output reaches the file, it will have a serious effect on the performance of your program. Therefore, this technique cannot be used in a production system since it will severely slow the execution of the program. In fact, large amounts of debug output produced in any kind of debug scenario for a production system will have a negative effect on the overall performance of the system. Debug output for production systems have to be carefully designed to have minimum impact on the performance of the system.

Log4c

Log4c is a small log library that we have written for you. This library is written entirely in C and can be used with either C or C++. The general concept of using it is that you first open a log file, and then write messages to the logfile. The message you write to the log file would typically show the values of variables at key points in your code and sometimes that tell you where you are in the code. You can also produce messages to tell you that the code has gotten itself into an erroneous situation.

There are three levels of messages you can send to the log file.

ERROR (L4C_ERROR) - This would be a very serious message indicating a major problem with the code that could result in erroneous output or a possible crash.

WARNING (L4C_WARNING) - A warning is less severe than an error but it still indicates that something is wrong with the program. Warnings are something that should be taken seriously even though they might not cause erroneous results or program termination.

INFO (L4C_INFO) - These are informational messages simply to tell the programmer that something has happened of interest inside the program. Debug messages are often informational so they can be removed from the production system.

When you are using the log4c library, you should interact with the Log4C data structures using the functions provided. These functions know how to manipulate the data structures correctly. Trying to manipulate the data structures yourself, without using the supplied functions, could corrupt the data structure. Each of the functions provided for you is described in the table below.

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

| l4cOpen | struct Log4cStruct l4cOpen(char fileName[], const int append); Open a log file and return a structure containing information about the log file. You must open a log file before it can be used. You should call l4cCheck() after opening the file to make sure that the file opened correctly. Parameter 1: fileName - the name of the file to open as a null terminated string. Parameter 2: append - a Boolean value which if false, will overwrite the file if it exists. If true, it will append to the existing file. Returns: A struct identifying the log file. |

| l4cClose | void l4cClose(struct Log4cStruct* log); This will close an open log file. Once the file is closed, it cannot be used again unless re-opened. Paramater1: log - the struct representing the log file to close. |

| l4cError | void l4cError( struct Log4cStruct* log, const char msg[]); Write an error message to the log file. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to write to. Parameter 2: msg - the text string to write to the log file. |

| l4cWarning | void l4cWarning( struct Log4cStruct* log, const char msg[]); Write an error message to the log file. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to write to. Parameter 2: msg - the text string to write to the log file. |

| l4cInfo | void l4cInfo( struct Log4cStruct* log, const char msg[]); Write an error message to the log file. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to write to. Parameter 2: msg - the text string to write to the log file. |

| l4cPrintf | void l4cPrintf( struct Log4cStruct* log, const int severity, const char format[], ...); Temporarily disable the log file without closing it. While disabled, writes will have no effect. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to write to. Paramater 2: severity - The severity of the message using L4C_ERROR, L4C_WARNING or L4C_INFO. Parameter 3: format - a format string, just like you would use for printf. Parameter 4, 5, ...: a varying number of arguments that will provide values to be used in the format string. |

| l4cCheck | int l4cCheck(const struct Log4cStruct* log, char errMsg[]); This checks the status of the log file and returns 0 if it is function normally. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to write to. Parameter 2: errMsg - if there is an error, a human-readable message will be placed in this string. The string must be declared to be of size L4C_ERROR_MSG_MAX + 1 or greater. |

| l4cDisable | void l4cDisable(struct Log4cStruct* log); Temporarily disable the log file without closing it. While disabled, writes will have no effect. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to disable. If a NULL parameter is passed, the function will have no effect. |

| l4cEnable | void l4cEnable(struct Log4cStruct* log); Enable the log file without closing it. This will resume writing to the file if it was disabled. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to disable. If a NULL parameter is passed, the function will have no effect. |

| l4cIsEnabled | int l4cIsEnabled(struct Log4cStruct* log); Determine if the log file is enabled and the messages will be written to the file. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to disable. If a NULL parameter is passed, the function will have no effect. Returns true if the file is enabled. If a NULL log file is passed, a negative value is returned. |

| l4cFilter | int l4cFilter(struct Log4cStruct* log, const int severity); This will filter the log file so that only messages of the indicated severity or higher will be written to the log file. If you set it to L4C_ERROR, you will only see errors messages in the log file. Setting it to L4C_INFO will send all messages to the log file. L4C_INFO is the default setting when a log file is opened. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to filter. If a NULL parameter is passed, the function will have no effect. Parameter 2: severity - the lowest severity to be sent to the log file. Returns: the previous setting of the filter. If log was NULL, returns a negative value. |

| l4cGetFilter | int l4cGetFilter(const struct Log4cStruct* log); This will return the current setting of the log filter. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to filter. Returns filter setting or negative value if log was NULL. |

| l4cDisableAutoFlush | void l4cDisableAutoFlush(struct Log4cStruct* log); Auto flush will flush a message to disk right after it has been written to the log file. This virtually guarantees all your messages will appear in the log file, even if your program crashes. The downside is that this has a major impact on performance if you are writing many log messages. The default is to have auto flush on. This function will disable auto flush if it is on. If the log is NULL, it has no effect. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to flush. |

| l4cEnableAutoFlush | void l4cEnableAutoFlush(struct Log4cStruct* log); Enable auto flush for the log file. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to flush. |

| l4cIsAutoFlush | int l4cIsAutoFlush(const struct Log4cStruct* log); Determine if auto flush is enabled for the log file. Parameter 1: log - the struct representing the log file to flush. Returns true if auto flush is enabled (default) or false if not enabled. Returns negative value if log is NULL. |

An example of usage of the log4c file is shown below.

#define _CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include "log4c.h"

int main(void)

{

char errMsg[L4C_ERROR_MSG_MAX + 1] = { 0 };

struct Log4cStruct log = l4cOpen("log.txt", 0);

if (l4cCheck(&log, errMsg)) printf("%s\n", errMsg);

else

{

l4cError(&log, "error msg");

if (l4cCheck(&log, errMsg)) printf("%s\n", errMsg);

l4cWarning(&log, "warning msg");

if (l4cCheck(&log, errMsg)) printf("%s\n", errMsg);

l4cInfo(&log, "info msg");

if (l4cCheck(&log, errMsg)) printf("%s\n", errMsg);

l4cPrintf(&log, L4C_INFO, "I am %d years old", 47);

if (l4cCheck(&log, errMsg)) printf("%s\n", errMsg);

l4cClose(&log);

}

return 0;

}

The contents of the file log.txt looks like:

[ERROR Sun May 22 10:02:14 2022]: error msg

[WARN Sun May 22 10:02:14 2022]: warning msg

[INFO Sun May 22 10:02:14 2022]: info msg

[INFO Sun May 22 10:02:14 2022]: I am 47 years old

Assertions

An assertion is a special type of statement that is often put into production code when you want to determine that something has gone terribly wrong with the program. When an assertion is triggered, it produces an error message and terminates the program. You would use an assertion only when you discovered a problem with the software that you knew there was no way to recover from. Terminating the program is a serious action not to be taken lightly. Many programs are doing important things and should not be terminated unless there is no other choice.

You can access insertions from the header file assert.h. This file defines a function assert(int). The integer parameter is really a Boolean and if it is false it will trigger the assertion. Typically, you insert an expression which will evaluate to give a boolean which is false when something is terribly wrong. For example, if a pointer can never have a value which is NULL you could use assert(ptr != NULL);. This would stop the program if the pointer ever did have the value of NULL.

Assertions like these are usually used to detect impossible situations. You often put assertions in to test for conditions which you are convinced can never happen. You insert these with the assumption that they will never be triggered. However, if they ever are triggered then this tells you that the impossible happened and that you need to take a very serious look at your program to determine what went wrong.

Lint

Lint is a program which is used to check source code. Programs like this do what is referred to as a static analysis of the code, which can detect many common mistakes. The functions of a lint program have largely been replaced by warning messages in modern compilers. However, lint programs are typically more sensitive than compilers and can still point out potential sources of errors that a compiler might miss. Therefore, when faced with a bug which eludes detection, you might want to use a lint program to help find it. Further, running a lint program on your source code might yield higher quality source code.

We will demonstrate this with an open source lint program for Windows called CPP check. You can download this program from https://github.com/danmar/cppcheck/releases/tag/2.8 .

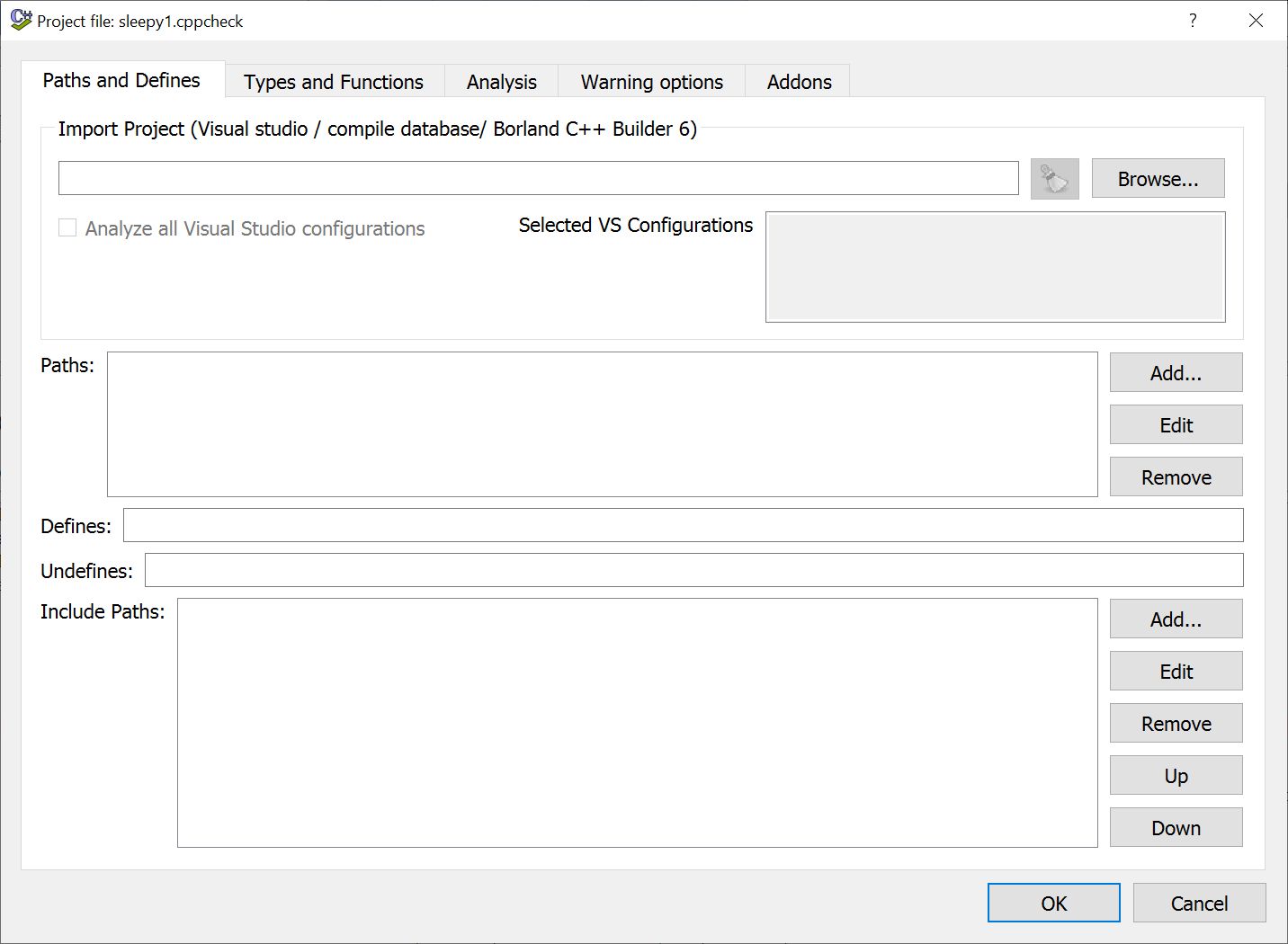

This program has a graphical user interface, which makes it a little easier to use. Like many programs, it uses a project file to tell it where the source and library files are. This can be set up manually, but it has the ability to directly read Visual Studio project files, which makes it very easy to run on Visual Studio projects. You can, of course, build your own project files which will check any source code files you have. The following show the interface to create a new project.

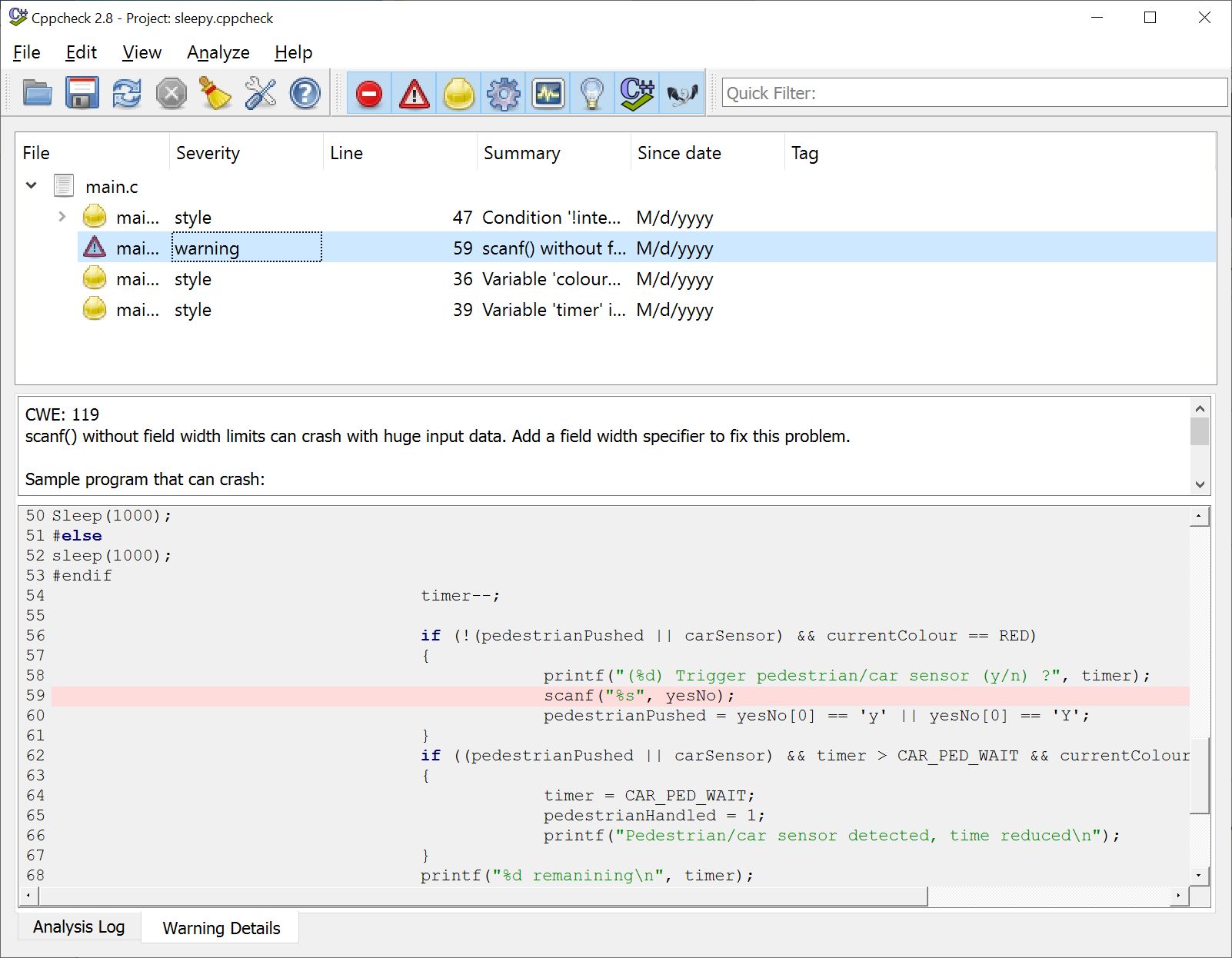

The browse button on the top right will let you select your Visual Studio project file and it will determine everything from that. If you need to set up a project yourself, you can set the source paths in the middle portion and include paths in the lower portion. Once the project is configured, it will analyze the code and show the ouput, as depicted below.

The list of warnings is at the top and you can click on on one and see the details and the line of code which caused the problem below.

This is one of many lint tools and similar tools are available for most languages. They can be particularly useful for weakly typed languages and scripting languages. For these languages, since parts of the code might seldomly be executed, they can detect errors before they occur.

Core Dumps

Core dumps are a much older debugging technique which are rarely used nowadays. A core dump makes a copy of all of the memory allocated for program and writes it to a file. This information is in binary and is very laborious to go through by hand. There are automatic dump readers which can allow you to explore these files in a more human readable way. These files normally contain all the binary instructions and data for the program and tell you where the program was when it terminated. This has become a last resort debugging technique which can be used after a program fails.

Conditional Compilation

Many people include debugging output statements in their code and make them conditional. For examnple:

#define DEBUG 1

...

if(DEBUG) printf("%s (%d): z=%d\n", __FILE__, __LINE__, z);

This allows them to easily turn debugging off and on by simply changing the value of the DEBUG macro. The downside of this technique is that there is a performance penalty every time it has to test the value of DEBUG at run time.

A more efficient solution to this problem is to use conditional compilation. This uses preprocessor directives to include or exclude code from the build based on the value of a macro. We can update the code above to use conditional compilation, as shown next.

#define DEBUG

...

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("%s (%d): z=%d\n", __FILE__, __LINE__, z);

#endif

This will include the printf in the code to be compiled if the DEBUG macro has been defined and exclude it if the DEBUG macro has never been defined. To remove the print statement from the code you just comment out the definition of the DEBUG macro. Since the print statement is removed from the code, it has no impact on performance and does not require a run-time test to determine if it should print.

Debug and Release Builds

Most of the Visual Studio projects are built in debug mode. The mode can be selected from a drop down near the top of the Visual Studio IDE. When in debug mode, the code is compiled such that:

- it links to a set of libraries which have been compiled in debug mode,

- It includes debugging information in an associated program database file that allows it to tell you exact line numbers on which errors occurred,

- It does not optimize the code to make it as fast as possible,

- It might include additional runtime checks to pick up errors that would normally not be picked up.

When you switch to release mode, it no longer includes all the debugging information into the project, links to libraries which were not compiled in debug mode, and runs the optimizer to produce the fastest running code possible. While you are developing your program, you should always build in debug mode. You should only switch to release mode when you are ready to produce a production version of your software. Although the debug versions will run much slower, they give you all the tools necessary to debug the program while it is under development.