Quality Assurance

In the early days of software development, quality assurance was almost overlooked. If the program worked and met minimal standards it was considered good enough. Over the years, software has grown larger, more complicated, and has been integrated into many aspects of our lives. Whereas in the early days software was run by professionals who could work around the many glitches that were found, as software migrated to use by the general population, it had to be of much higher quality. As a result of this, quality assurance, once relegated to an afterthought, has become an important part of the software development process.

Software quality assurance is a process to assure that all parts of the software development process are monitored and comply with relevant standards and meet all project requirements. There are quality assurance standards like ISO 9000 and others that might need to be complied with. Modern software quality assurance looks at the entire software development lifecycle from gathering requirements, to design, coding, and even documentation. We will focus on software quality assurance aimed at coding and ensuring that the resulting code is of high quality and meets the requirements.

The rest of this section will look at some of the documents we need to produce as part of the quality assurance process and then we'll move on to look at how we can use software tools to help us manage the entire process.

Agile Projects

Traditional project management was driven by due dates. The project was laid out in terms of deliverables and dates assigned to each one. This was typically done using something like a Gantt chart where you could show what work could be conducted in parallel or what work was dependent on other work being finished first. There were two problems with this approach. The first was that it was inflexible so that any unexpected event in the preparation of a deliverable would require a complete rescheduling of all deliverables after that. The second problem was that if a deliverable turned out to be more complicated than initially thought, there was no way to easily break it down into smaller units of work. As a result of these shortcomings, this type of project management was usually doomed to failure.

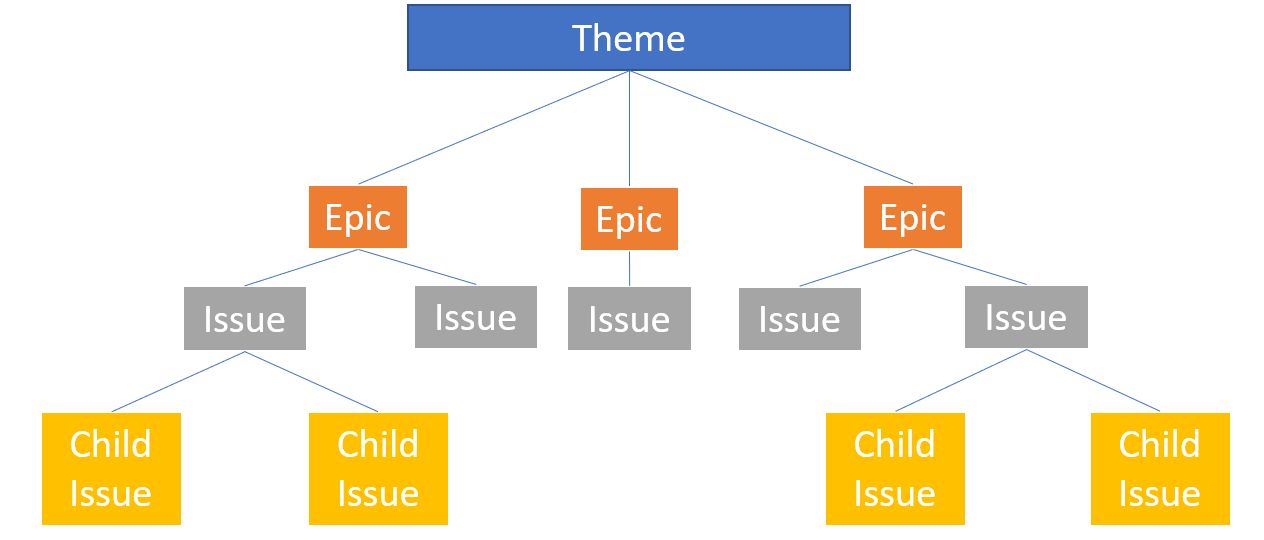

The agile approach to project management has a much more flexible way of breaking down the tasks that need to be done to complete a project. Agile breaks down a project into themes or initiatives, epics or projects, and tasks or issues. We will explore each of these below.

Themes

A theme is one of the major goals of the project. It is usually a long term objective that is a major and significant component of the project. A theme can also be viewed as a major strategic business objective. For example, if you decide you want to break into the project management software market then this would be the theme of your project. Of course, a theme is too broad an objective and it needs to be broken down into smaller, more manageable objectives.

Epics

An epic is a larger body of work that constitutes one of the main components of a theme. Epics are typically measurable which means that you can readily determine when they have been completed. For our example of penetrating the project management software market, we might layout the following two epics:

- New features - an effort to develop new features for our project management software,

- Enhancement - and effort to enhance the current features of our software to make it suitable for use by project managers.

These epics are major pieces of work which need to be broken down into smaller, more manageable steps.

Issues

An issue it is one of the tasks that needs to be completed as part of an epic. An issue is a small enough task that it can be performed in a reasonable amount of time, say a few days or a week. Issues are readily actionable which means that you can easily do work to complete them. For the new features epic of our attempt to penetrate the project management software market, we could break it down into 3 issues:

- Researching the project management tool market,

- Designing new features that we want to implement,

- Developing the new features that we are going to implement.

Each of these issues is still fairly large and it can be broken down further into child issues or sub-tasks. Sub-tasks could be created to break it down into more manageable units or it could be broken down based upon the skills necessary to perform the sub-task.

The breakdown into themes, epics and issues is highly flexible and can be changed at any time to reflect changes in the project. This could be a change in requirements or a realization that new issues need to be created due to the size of an epic or another problem.

User Stories

In the traditional management process, individual tasks were created based upon the technical needs of the project and contained lots of details of the technical work that needed to be performed. The problem with this was that it missed the big picture. The developer did not see how this small work item fitted into the larger picture and what functionality it was going to deliver to the end user.

In an effort to keep the developers informed of the importance of what they're working on and to let them see how it fits into the big picture, it has been common to specify tasks as user stories. The user story is a small piece of work that represents some kind of functionality that the end user wants implemented. The implication is that rather than building technical details, we now build units of functionality that are needed by the end user.

User stories are effective because they convey the user's perspective to the developer and they are also specified in terms that the customer can readily understand. By focusing on the customers needs, we do not lose focus and deliver what the customer wants. User stories create a shared understanding amongst all shareholders in the project so that everybody knows what is being developed and why. User stories also allow us to prioritize the work items based upon their value to the business.

As an example of a user story, consider:

As a visitor to the project management website, I want to be able to filter the different projects based upon the project name as well as the personnel working on the project.

You should write your user stories so that they define when the story is done. In other words, they should make it obvious when this task is complete and they should contain something that tells us how we can test to determine when the task has finished.

User stories usually correspond to an issue but that does not mean that they are atomic units. Issues can be broken down further into child issues or sub-tasks. These child issues can, of course, have their own user stories attached to them.

Each user story should be INVESTable:

- Independent - the story should not depend on other stories and can be completed on its own,

- Negotiable - it should open a conversation with the customer to invite refinement and change,

- Valuable - it should provide significant value to the project,

- Estimable - it should be estimated to be the right size for an issue,

- Small - it should be able to be completed in a few days,

- Testable - it should have clear acceptance criteria so tests can be writtten to verify it.

Kanban Boards

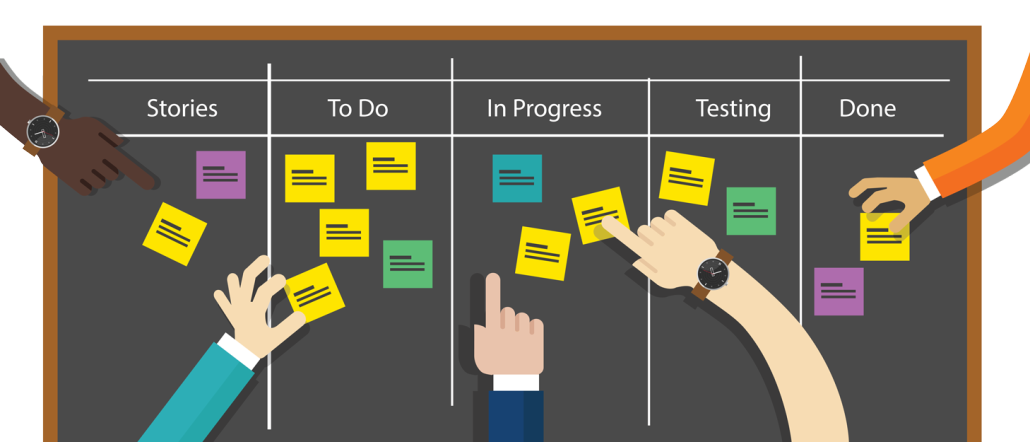

A Kanban board displays the progress of our project as three or more columns. At its simplest, a Kanban board has a list of requested issues in the first column, issues which are in progress in the middle column, and issues which are completed in the right column.

| Requested | In Progress | Done |

|---|---|---|

| Implement skeletal architecture |

The first Kanban board was developed in the 1940s for Toyota automotive in Japan. The goal was to control and manage work and inventory at every stage of the production process. Kanban is an inherently visual display of the progress of work in a system. The columns represent the steps in the overall process and the position of items in the columns allows you to visually see exactly where things are on their way through the process. By adding columns to the Kanban board, you will be able to tailor the board to the software process you are using.

To use a Kanban board, issues start out in the leftmost column until people are ready to start working on them. Once they have started, they can be moved to the middle column to show that the issues are being worked on. Finally, once all of the work on the issue has been completed, the issue is moved to the done column on the right. We are free to add more columns to our Kanban board as necessary for our particular project. In our situation, where were we will be dealing with quality assurance issues, we can add an extra column to represent the quality assurance process.

| Requested | In Progress | QA | Done |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implement skeletal architecture |

One of the things you can use a Kanban board for is to limit the amount of work in progress. Many of the tools that use the Kanban method allow you to put a limit on the number of issues which can be placed in any of the in-progress columns. This is to ensure that your team is not overloaded by having too many issues in progress at the same time.